In previous posts we noted that most animals’ behavior is pretty well circumscribed by their natural instincts and limited intelligence; they don’t have true agency, by which I mean two things: 2) the ability to choose and 2) moral agency. That’s why they can’t be held morally culpable for what they do, even if we disapprove or disallow it. (I have zero interest here in discussing whether or not free will exists, I unrepentantly assume it does).

No one ever jailed a tiger for killing to eat, but we certainly do kill man-eating tigers if we can. In both cases, it boils down to the same thing; tigers are remorseless killing machines. Even if individual tigers can be trained to be relatively peaceful and can show affection, they do not show any evidence that they can or would reject their natural instincts.

You might be saying, ‘well of course, they are wild animals! What do you think you’ve shown?’ Well I’ll admit its an easy case, but really, squirrels, toads, and all manner of creatures great and small are in the same boat and we don’t think of them as ‘wild’. But I suppose what you want to point out is that some animals, such as dolphins, dogs, pigs and great apes seem to be different; they are way smarter and highly social. And that combination must count for something in the rankings. Those are interesting examples and no doubt interesting cases can be made that these animals sometimes seem to exhibit moral agency. But for now I’m going to say that the only real candidates here are dogs and maybe dolphins (sorry to Babe, Porky and Wilbur) and table it – but I promise to say a bit more about that a few posts down the road.

So, what I’m saying is outside of a very few possible exceptions, human beings are unique in being true agents. And even then I qualify that by acknowledging that many of often don’t follow through on our ability to make choices. This all brings me to the million-dollar question – when do we judge humans to be good or bad, when do we judge behavior to be right or wrong? Do you see the issue? If we don’t blame a tiger for being a killer, and we don’t (rightfully) blame a dog for barking, because they can’t really choose, then why do we blame humans for negative consequences from actions they didn’t choose to do?

Well we certainly do, but we also do make distinctions such as between murder and involuntary manslaughter. We punish both, the former much more severely than the latter. And that’s because of the difference between voluntary and involuntary action.

Human beings have will or agency, we can knowingly do things, we can choose to do otherwise. How we do, and why we sometimes don’t is at the core of ethics. So lets dig into the difference between voluntary and counter-voluntary action.

I didn’t mean to do that!?!

Either you meant to do something or you didn’t, right? You probably think that, but then you probably also kind of believe in the point behind the “Freudian slip”; there are no accidents.

Well Aristotle did believe there are some accidents. In fact he thought that it was of the utmost importance to carefully study what it means to say actions are voluntary or counter-voluntary. And a major reason why is because what a mess the emotions can make of our distinction. After all, we say things like ‘fit of rage’, ‘consumed by jealousy’ and ‘blinded by love’. But does that mean the emotions make us animalistic? I agree with Aristotle that the answer to that is ‘Hardly! Some emotional actions are voluntary and some are involuntary because 1) some are controllable and should be controlled, 2) some are controllable and shouldn’t be so controlled, and 3) others cannot be controlled!’ So let’s get to understanding what’s going on.

A couple of definitions

Keep in mind that in philosophy we are really fanatical about definitions, and as a result consensus can be very hard to come by, but the process is very important to both deeper understanding of related issues and they are a key component in a successful argument. As a result, philosophical definitions are tightly packed and need to be unpacked. Let’s look at the definition for a Voluntary Action to see what I mean.

A Voluntary Action is an action that depends on you, that you do knowingly, and not under coercion. Remember that in the last post we argued that humans have the singular talent of being able to deliberate. We can think ahead about how to achieve specific goals, and that’s what makes us human. Well, what that means is that if you deliberate on a particular out come, you understand the relevant contextual factors, and are not forced to act in any way, what you do is a voluntary act.

Aristotle lists four relevant contextual factors and if you meet the criteria in a specific situation, then you in fact know what is happening. If you miss any of the four you don’t really know what is happening.

1) Who is acting, in relation to what, or affecting what?

2) With what are they acting? (e.g. a scalpel or a sword?)

3) What is the action for? (e.g. to save a life, to obtain someone’s money)

4) How is it done? (gently, vigorously, etc)

For example, say last Sunday you remembered it was Mother’s Day, you love your mom, she is alive, you believe that she did a pretty okay job raising you, you get along well enough, you both have phones you can use, and your dad wasn’t holding a gun to your head. If you picked up your phone and called her to tell her how much you love and appreciate her, and succeeded in doing so, making her feel all the sleepless nights were worth it, then you did so voluntarily. You were the actor, you used a phone, you did it to make your mom feel loved, and you did it with affection. Blam. Voluntary action on your part.

Of course, the flip side is counter-voluntary action: Anything you do that doesn’t depend on you, that you do in ignorance, or under force, is counter-voluntary. So for example, you are growing older (and wiser) every day, but it’s not quite right to say you are ignorant of it or being ‘forced to’ do so. Instead we say it doesn’t depend on you, it just happens that way.

Now here’s the reason we made it a point early to understand that humans can deliberate even if we don’t always do so. It turns out to be a pretty important issue: because of it, our definition actually allows for two types of voluntary action. There are voluntary actions that you did deliberate about and voluntary actions you did not deliberate about. (And that means, among other things, that just because you did something on a whim doesn’t mean its not your fault or that you didn’t mean to.)

Putting it all together, what we’re saying is that some voluntary actions are deliberated beforehand while others are not, instead they are performed without having decided to do them. (Remember that deliberation is a sort of calculating backwards from a stated goal all the way back to your conscious agency that leads to a decision on what action to take in order to set the sequence leading to your goal in motion, and it can happen quite quickly.)

Concluding with an example

It might be surprising and it may even sound wrong, but we’re going to argue pretty consistently and aggressively that you can in fact do something knowingly but without prior deliberation. To Aristotle’s mind, while a truly virtuous person (like grandma, maybe) always discriminates correctly, most of us fail in our discrimination, the implementation of our discrimination, or at both. The main way we do this is to act in possession of our faculties yet hurriedly such that we don’t think through the consequences – and regretting them when they happen. We meet all four criteria but we didn’t think through to our goal in advance.

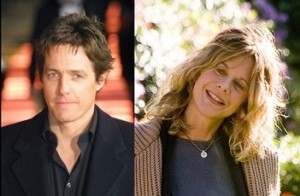

Consider most any romantic comedy you’ve ever seen. The lead actor, probably Hugh Grant, plays some “regular guy” on his way to do “regular guy stuff”, like go see his fiancée give a lecture at a book store. (She’s probably played by Julia Roberts). And as he walks down some New York City street being absentminded, goofy and charming all at once in his special way, he arrives at the corner only to see a suitably adorable woman (probably Meg Ryan) sitting at a table on the restaurant’s patio. Hugh, not yet seen by Meg, of course immediately sits down at a table near by and cleverly covers his face with his upside-down menu so he can watch her sip wine and write letters. (And of course he’ll soon regret it when her boyfriend, probably Jude Law, startles him and Hugh spills red wine all over his shirt.)

Did or Didn’t Hugh act knowingly here, and did he ‘deliberate’? Let’s go over Aristotle’s checklist:

1) Who was acting? Hugh is not yet insane so he is well aware that he is acting and in relation to a pretty lady.

2) He has no apparent tools but perhaps his boyish charm, affable manner and British accent.

3) The action is for getting near the pretty lady and perhaps meeting her.

4) It is done sheepishly, even boyishly, of course.

He meets the criteria so he is definitely not acting in ignorance, he is acting knowingly. And he’s not under coercion – humans don’t go into heat. And clearly it depends on him. So he has acted voluntarily. You may want to say that he still might have deliberated on the issue, but then you’re just being difficult. We’ve all been in situations where we acted all of a sudden. We suddenly want pizza, or to go to the book store, or to walk down this street instead of that one. Its really stretching the notion of “deliberation”, but its not at all stretching the idea of “knowing” what you’re doing.

Next time we’ll try to decide whether Hugh was a bad person by discussing impulsiveness, weakness, and finalizing our discussion of knowing what you are doing.

No one ever jailed a tiger for killing to eat, but we certainly do kill man-eating tigers if we can. In both cases, it boils down to the same thing; tigers are remorseless killing machines. Even if individual tigers can be trained to be relatively peaceful and can show affection, they do not show any evidence that they can or would reject their natural instincts.

You might be saying, ‘well of course, they are wild animals! What do you think you’ve shown?’ Well I’ll admit its an easy case, but really, squirrels, toads, and all manner of creatures great and small are in the same boat and we don’t think of them as ‘wild’. But I suppose what you want to point out is that some animals, such as dolphins, dogs, pigs and great apes seem to be different; they are way smarter and highly social. And that combination must count for something in the rankings. Those are interesting examples and no doubt interesting cases can be made that these animals sometimes seem to exhibit moral agency. But for now I’m going to say that the only real candidates here are dogs and maybe dolphins (sorry to Babe, Porky and Wilbur) and table it – but I promise to say a bit more about that a few posts down the road.

So, what I’m saying is outside of a very few possible exceptions, human beings are unique in being true agents. And even then I qualify that by acknowledging that many of often don’t follow through on our ability to make choices. This all brings me to the million-dollar question – when do we judge humans to be good or bad, when do we judge behavior to be right or wrong? Do you see the issue? If we don’t blame a tiger for being a killer, and we don’t (rightfully) blame a dog for barking, because they can’t really choose, then why do we blame humans for negative consequences from actions they didn’t choose to do?

Well we certainly do, but we also do make distinctions such as between murder and involuntary manslaughter. We punish both, the former much more severely than the latter. And that’s because of the difference between voluntary and involuntary action.

Human beings have will or agency, we can knowingly do things, we can choose to do otherwise. How we do, and why we sometimes don’t is at the core of ethics. So lets dig into the difference between voluntary and counter-voluntary action.

I didn’t mean to do that!?!

Either you meant to do something or you didn’t, right? You probably think that, but then you probably also kind of believe in the point behind the “Freudian slip”; there are no accidents.

Well Aristotle did believe there are some accidents. In fact he thought that it was of the utmost importance to carefully study what it means to say actions are voluntary or counter-voluntary. And a major reason why is because what a mess the emotions can make of our distinction. After all, we say things like ‘fit of rage’, ‘consumed by jealousy’ and ‘blinded by love’. But does that mean the emotions make us animalistic? I agree with Aristotle that the answer to that is ‘Hardly! Some emotional actions are voluntary and some are involuntary because 1) some are controllable and should be controlled, 2) some are controllable and shouldn’t be so controlled, and 3) others cannot be controlled!’ So let’s get to understanding what’s going on.

A couple of definitions

Keep in mind that in philosophy we are really fanatical about definitions, and as a result consensus can be very hard to come by, but the process is very important to both deeper understanding of related issues and they are a key component in a successful argument. As a result, philosophical definitions are tightly packed and need to be unpacked. Let’s look at the definition for a Voluntary Action to see what I mean.

A Voluntary Action is an action that depends on you, that you do knowingly, and not under coercion. Remember that in the last post we argued that humans have the singular talent of being able to deliberate. We can think ahead about how to achieve specific goals, and that’s what makes us human. Well, what that means is that if you deliberate on a particular out come, you understand the relevant contextual factors, and are not forced to act in any way, what you do is a voluntary act.

Aristotle lists four relevant contextual factors and if you meet the criteria in a specific situation, then you in fact know what is happening. If you miss any of the four you don’t really know what is happening.

1) Who is acting, in relation to what, or affecting what?

2) With what are they acting? (e.g. a scalpel or a sword?)

3) What is the action for? (e.g. to save a life, to obtain someone’s money)

4) How is it done? (gently, vigorously, etc)

For example, say last Sunday you remembered it was Mother’s Day, you love your mom, she is alive, you believe that she did a pretty okay job raising you, you get along well enough, you both have phones you can use, and your dad wasn’t holding a gun to your head. If you picked up your phone and called her to tell her how much you love and appreciate her, and succeeded in doing so, making her feel all the sleepless nights were worth it, then you did so voluntarily. You were the actor, you used a phone, you did it to make your mom feel loved, and you did it with affection. Blam. Voluntary action on your part.

Of course, the flip side is counter-voluntary action: Anything you do that doesn’t depend on you, that you do in ignorance, or under force, is counter-voluntary. So for example, you are growing older (and wiser) every day, but it’s not quite right to say you are ignorant of it or being ‘forced to’ do so. Instead we say it doesn’t depend on you, it just happens that way.

Now here’s the reason we made it a point early to understand that humans can deliberate even if we don’t always do so. It turns out to be a pretty important issue: because of it, our definition actually allows for two types of voluntary action. There are voluntary actions that you did deliberate about and voluntary actions you did not deliberate about. (And that means, among other things, that just because you did something on a whim doesn’t mean its not your fault or that you didn’t mean to.)

Putting it all together, what we’re saying is that some voluntary actions are deliberated beforehand while others are not, instead they are performed without having decided to do them. (Remember that deliberation is a sort of calculating backwards from a stated goal all the way back to your conscious agency that leads to a decision on what action to take in order to set the sequence leading to your goal in motion, and it can happen quite quickly.)

Concluding with an example

It might be surprising and it may even sound wrong, but we’re going to argue pretty consistently and aggressively that you can in fact do something knowingly but without prior deliberation. To Aristotle’s mind, while a truly virtuous person (like grandma, maybe) always discriminates correctly, most of us fail in our discrimination, the implementation of our discrimination, or at both. The main way we do this is to act in possession of our faculties yet hurriedly such that we don’t think through the consequences – and regretting them when they happen. We meet all four criteria but we didn’t think through to our goal in advance.

Consider most any romantic comedy you’ve ever seen. The lead actor, probably Hugh Grant, plays some “regular guy” on his way to do “regular guy stuff”, like go see his fiancée give a lecture at a book store. (She’s probably played by Julia Roberts). And as he walks down some New York City street being absentminded, goofy and charming all at once in his special way, he arrives at the corner only to see a suitably adorable woman (probably Meg Ryan) sitting at a table on the restaurant’s patio. Hugh, not yet seen by Meg, of course immediately sits down at a table near by and cleverly covers his face with his upside-down menu so he can watch her sip wine and write letters. (And of course he’ll soon regret it when her boyfriend, probably Jude Law, startles him and Hugh spills red wine all over his shirt.)

Did or Didn’t Hugh act knowingly here, and did he ‘deliberate’? Let’s go over Aristotle’s checklist:

1) Who was acting? Hugh is not yet insane so he is well aware that he is acting and in relation to a pretty lady.

2) He has no apparent tools but perhaps his boyish charm, affable manner and British accent.

3) The action is for getting near the pretty lady and perhaps meeting her.

4) It is done sheepishly, even boyishly, of course.

He meets the criteria so he is definitely not acting in ignorance, he is acting knowingly. And he’s not under coercion – humans don’t go into heat. And clearly it depends on him. So he has acted voluntarily. You may want to say that he still might have deliberated on the issue, but then you’re just being difficult. We’ve all been in situations where we acted all of a sudden. We suddenly want pizza, or to go to the book store, or to walk down this street instead of that one. Its really stretching the notion of “deliberation”, but its not at all stretching the idea of “knowing” what you’re doing.

Next time we’ll try to decide whether Hugh was a bad person by discussing impulsiveness, weakness, and finalizing our discussion of knowing what you are doing.