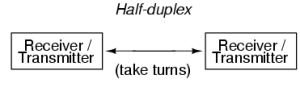

The main development or change in how Descartes understands the mind from Meditations on First Philosophy to Passions of the Soul is that in this latter book his theory makes it possible for the body to act without the mind. In fact, I argue, he doesn’t leave the mind any way to affect the body at all even though he of course wants it to. There are a couple of reasons for this state of affairs. First, as we saw in the first Cartesian Error, he argues that the only thing the mind can do is think, and the body cannot think at all. Then in the Second Error, he argues that emotions aren’t thinking and explains that the human body works in such a way as to be able to start, continue and end emotions and emotion-based behavior. I call this organization, this explanation, an example of half-duplex communication between body and mind, a type of communication I previously said was exemplified by walkie-talkies and text messages. Let’s briefly review why this can’t be a reasonable way to look at how the mind and body interact.

If the mind were like a walkie-talkie, by definition only one end at a time can communicate. So if you had a spider on your leg, what would have to happen for you to get rid of it? First, the body would feel the pressure on your flesh. But for your mind to know the spider was there too would require one of four things, all of which have problems and raise more questions than they answer, (at least for Descartes):

1) That by a stroke of luck, at the same moment when the body felt the pressure, the mind happened to not be communicating out any messages and so is able to receive transmission, OR

2) The body not only feels the pressure on the skin, but also “knows” that the mind should stop transmitting and instead listen, and can force the mind to do so by accompanying important messages with a message such as “over” to tell the brain to start talking, OR

3) The body itself would just “know” how to stop the bug (like a reflex), OR

4) The body is constantly transmitting messages whether or not the mind is in a position to hear them, and sometimes it listens in for whatever reason.

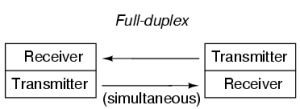

On the other hand, Plato, Aristotle and Lucretius argued for something different, an interactive and reciprocal communication between the body and the mind (and the emotions), a process I called duplex communication. For them, the mind and the body are both duplex transmitters, such as cellular phones, which allow two constantly running communications to both be understood by their targets.

This not only fits common sense and firsthand experience, but our more advanced understanding of the body tells us this is correct. Duplex communication between the brain and the rest of the nervous system throughout the body allow for immediate response to outside stimuli by real-time measurement and analysis – Plato, Aristotle and Lucretius each saw that the body feels things that don’t quite rouse the mind, and that our bodies are actually sentient – aware – in a way akin to the way the mind is. The duplex process also allows for conscious analysis of the stimuli, the body’s responses, the results of the responses, what goals are being achieved, and what goals might be better, as well as the ability to seek after those goals. The body can run “on its own” but a conscious person can study her reactions and change her behavior to her preference. After all, they are made of the same stuff. Half duplex communication doesn’t allow this.

So the third Cartesian Error is that the theory cannot explain how the mind and body could have duplex communication, which the P-A-L theory gave an excellent argument for, and which I conclude is a fundamental aspect of the emotions backed up by contemporary research. More specifically, third error has to do with how Descartes thinks the mind and body communicate with each other.

Descartes’ half-duplex theory argues that the mind/soul is united to all parts of the body, not just the pineal gland (If you read carefully this theory is also there in Meditation VI) but that the soul is able to exercise its unique function – thinking – best in the pineal gland (and its my opinion that he really does think of it as more physically extended than he is usually given credit for). He says that the soul and body act on each other by taking turns “radiating”: as in the soul “radiates” into the rest of the body from the pineal gland. Think of it as sort of like an x-ray in reverse. Instead of shooting x-rays through our body to give us an image of our body, things like bears shoot ‘bear-rays’ at our eyes. A similar process happens from the pineal gland to the soul and vice versa. This is completely incorrect but such particulars don’t really matter. What matters is that he has in mind a physical process by which he thinks we receive our sensory information, and it works like in the diagram above. Think of sending a text or SMS message to a friend with your cell phone. Basically, what happens is that a message goes from your phone to an SMS site, and the site attempts to deliver your message to the other phone. If it is ‘delivered’, your friend can read and reply in the same manner.

Descartes’ half-duplex theory argues that the mind/soul is united to all parts of the body, not just the pineal gland (If you read carefully this theory is also there in Meditation VI) but that the soul is able to exercise its unique function – thinking – best in the pineal gland (and its my opinion that he really does think of it as more physically extended than he is usually given credit for). He says that the soul and body act on each other by taking turns “radiating”: as in the soul “radiates” into the rest of the body from the pineal gland. Think of it as sort of like an x-ray in reverse. Instead of shooting x-rays through our body to give us an image of our body, things like bears shoot ‘bear-rays’ at our eyes. A similar process happens from the pineal gland to the soul and vice versa. This is completely incorrect but such particulars don’t really matter. What matters is that he has in mind a physical process by which he thinks we receive our sensory information, and it works like in the diagram above. Think of sending a text or SMS message to a friend with your cell phone. Basically, what happens is that a message goes from your phone to an SMS site, and the site attempts to deliver your message to the other phone. If it is ‘delivered’, your friend can read and reply in the same manner.

Here is a “play by play” of his argument:

1) the soul is truly joined to the whole body, no part is excluded,

2) because of the centrality of the [pineal] gland’s location the soul can perform its function in a more particular way there than anywhere else,

3) The central location of the pineal gland allows the soul to “better alter the course of the spirits (chemicals) with the slightest movement”.

4) Similarly, the slightest change in the course of the spirits can greatly change the movements of the pineal gland, affecting the soul greatly.

5) This activity can happen because of the “mediation” of the spirits and the nerves and blood that carry them.

6) Our bodies use “fire” or “heat” to make all possible movements, and it is wrong to think that the soul can impart either to our bodies (A5-A8).

So what we’ve learned here is that because

A) Descartes has a complete, purely physical account of how sense perception and muscular movement are possible,

B) we have all manner of non-conscious motion (eating, breathing, walking aimlessly, etc) and

C) He firmly argues the soul imparts no motion to the body,

then it is fundamentally impossible on his theory for duplex communication to occur between the mind and the body. In fact, it seems impossible for him to seriously, coherently defend any meaningful communication between them. At best what he has is a “half-duplex” system, but that doesn’t match reality and it couldn’t work, as we discussed briefly in the sections on Lucretius.

The next post, the last one to focus on Descartes, will discuss the ethical implications of the three Cartesian Errors.