As I said earlier, Lucretius thinks the mind controls cognition and the particles it is made up of are localized in the chest. On the other hand, anima, the vital spirit, is everywhere else in the body but the mid breast. Vital spirit’s particles move to the sway of mind particles and give the body sensation; thanks to vital spirit “even the teeth share in sensation”. Keep that in mind as we talk below about "registering" and "bodily awareness".

The View from 10,000 Feet

Echoing Plato’s analogy of the psyche with a country, where the rational part is the leaders and the spirited part is the military,

Lucretius says that while mind rules, vital spirit is the “body’s guard and cause of health”. It’s a safety mechanism to protect your flesh. In fact, vital spirit and flesh “twine together with common roots” and he thinks trying to tear them apart would be all but impossible, like taking separating the scent out of curry. He also describes it as being so thin and light, so sensitive, that even thoughts can make it move.

Getting Our Hands Dirty

Now that we have the basics on what mind and vital spirit, animus and anima, are, its time to get down to brass tacks. We’ve noted that Lucretius is a strict physicalist, believing that everything that exists is made out of physical particles. And he thinks that mind and spirit are one and the same thing, yet that mind is cognitive and spirit is not. But why should the same substance be able to act so differently?

Isn’t that paradoxical, or worse, impossible? Well, to avoid that conclusion he’s going to need to give us a satisfactory explanation for this apparent strangeness.

The reason, he says, why they can be the same “stuff” but act so differently is that while the mind is affected the same way as the body, vital spirit is “not one and simple”. What he means is that there are different properties to mind and spirit, they are not pure and simple like, say, hydrogen, carbon or iron. Instead mind and spirit are two subtypes of the same basic type of stuff, an “uber-soul” material, vital spirit. And vital spirit is not a basic element either. It’s a mixture of some sort, like water or soda.

We don’t need to go into the actual physical stuff he thinks make up vital spirit, the mind and spirit because its just not even close to being right as far as what we know to be the components of the nervous system. How could it have been, it would be about 1,500 years before the microscope was invented,

and roughly another 360 before the Electroencephalograph (EEG, the measurement of the electrical activity of the brain) became widely available.

But if you’re interested in knowing more, contact me and I’ll send you my fairly detailed discussion of it from my dissertation.

Whatever physical bits it is actually made of, in practice this vital spirit is basically what we’d call “bodily awareness”, the mechanism that allows us to do things like avoid running into people walking past us the other way even by the slimmest of margins. And as I’ve said before, given the way he describes them it’s fair to think of its components, animus and anima, as what we’d say are aspects of our overall nervous system.

So to put a bow on it, he is saying that the best explanation for our capabilities is that there is a physical system spread throughout the body that is responsive to outside stimuli, and that is directly connected to a centralized core, made of the same material. This core component uses in various ways the input to guide the actions/responses of the whole being. This centralized material, when activated by the spread-out system, is able to think and feel to varying degrees. Or as we’d say today, the nervous system allows for or creates the initial conditions for basic things like reflexes but also for our ability to measure and judge, and our ability for abstract thought.

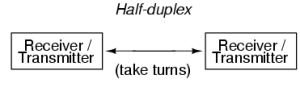

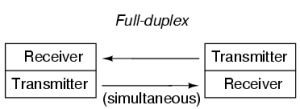

Let’s be clear: Lucretius does not think that the chest-brain-stuff (animus) simply takes in data from the anima, stops the flow and considers the data, then sends commands to a body that is silently waiting. Instead the components that make up vital spirit allow for duplex communication between the brain and the rest of the nervous system throughout the body. It allows for immediate response to outside stimuli by real-time measurement - he explains that the body feels things that don’t quite rouse the spirit, and that our bodies are actually sentient – aware – in a way akin to the way the mind is. But this duplex process also allows for conscious analysis of the stimuli, the body’s responses, the results of the responses, what goals are being achieved, and what goals might be better, as well as the ability to seek after those goals. The body can run “on its own” but a conscious person can study her reactions and change her behavior to her preference. After all, they are made of the same stuff.

Yet its interesting to note and accept with Lucretius that our bodies register a lot more info than we ever actually register consciously. Think of micro-facial expressions, gut reactions, goose bumps, mosquito bites, or even navigating foot traffic on a busy sidewalk. These are all clearly things the body “notes” – or as I will put it sometimes, registers – even though you as a thinking person aren’t aware. And common sense tells us he’s right: not only are we not conscious of things such as mosquitoes biting us, we have no feeling whatsoever of things such as radiation, yet clearly our body registers it, sadly, to very poor results.

Emotion

Lucretius thinks that emotions are qualities of both animus and anima; they both process and communicate information, and so they can’t be irrational. But its hard for him to call them rational too. He’s convinced that emotions are felt physically in the heart and concludes in part from this that the mid-region of the breast is the seat of intellect and mind. But just because they are felt there doesn’t mean they are only felt there. In fact, he believes that there is more than one kind of emotion; one more or less purely mental (but of course physical) and “spirit-based” or “visceral” emotion that is much deeper and stronger but of course still “cognitive”.

On Lucretius’ account, due to the interactions of the physical particles that make up vital spirit, the mind emotes in an interesting way. Basically, anyone in an emotionally charged situation, anyone emotionally agitated, ends up at whatever emotion they end up at (or calm) by going through a progression from the burn of anger, to the chill of fright, and eventually back to calmness, as the duplex communication between the mind and spirit continues. Whether true or not, given the importance that anger and fear responses have to survival this makes some sense. These emotions are utterly important to our survival. The problem of course is that they can sometimes be a little antiquated and therefore lead us to misunderstand what our best reactions to a perceived stress should be.

The idea is that for some emotions, say fear for instance, up to a certain threshold only the mind is “emoting”, but there is a tipping point where the vital spirit is roused. As such, the chest-brain area is usually the part handling (and ‘showing” fears, but after a point the whole spirit system gets involved and you see other behaviors related to fear.

He also explains that while vital spirit moves to the “sway” of the mind, it does not always follow mind’s influence. At least sometimes, perhaps even most of the time, it does, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Whether it does or doesn’t depends on what beliefs are followed. When incoherent or mistaken beliefs are followed, we get bad desires and bad results. When correct beliefs are followed we get good desire and satisfaction. So to the extent an emotion keeps you from making a smart choice, or makes you feel like doing something stupid, or counter-productive, they would seem to be irrational, yet the real thing to blame here is not that system, its job is to protect your body, and its perceiving a threat!

But the animus! It’s the job of the animus to be rational, to oversee things. If the mind doesn’t do its job the times when it is within its power to do so, then the cause must be a physiological limitation, stupidity, laziness, or bad character. Nothing about emotions, or mind, or spirit makes it have to be that emotions and emotional responses have to be irrational or bad.

Conclusion

So we’ve seen Lucretius follow Plato and Aristotle very closely in some fundamentally important respects: 1) He’s keenly sensitive to the impact the emotions can have on other thoughts and on actions; 2) He believes there are two types of emotions; one more or less purely ‘mental’ and one ‘spirit-based’; more visceral and deeply felt, but still cognitive. (Of course both are still purely physical.) While some, say an existential dread, are cases where the mind is by and large the only part emoting, there may be a threshold past which the vital spirit is roused. Similarly, there can be emotions, say fear of a predator, that are more basic and active at the level of the spirit, but past a certain point the rest of the spirit system, the mind, may get involved; 3) he believes in duplex communication between the ‘mind’ and the body, and that 4) the mind and the body are both physical. In sum, he’s in basic agreement with Plato and Aristotle’s insights on ethics and psychology. At the very least nothing they said is directly contradicted by Lucretius.

The improvement Lucretius makes is that he not only understands that there must be a physiological explanation to all this, he tries to explain it. At length. And with some very imaginative, even penetrating insights. In fact, it was absolutely state-of-the-art science for 55 B.C. In fact, it was pretty state-of-the-art for a lot longer than that!

Combining the thoughts of Plato, Aristotle and Lucretius on the emotions, the mind, and ethics, we can see a pretty well worked out, defensible position. I call it the P-A-L account, and I call the theory of emotions in the P-A-L account the “pluralist account” of emotions. That’s in comparison to the visceral account, first developed by Homer, and the third candidate-account, which we're about to start discussing, cognitivism.

Review and Preview

We have a “scientific” (physiologically centered), state-of-the-art for its time explanation of how the mind and body are parts of a functioning system, how they interact and impact each other, and what thinking and the emotions are. And it all fits in just fine with the psychological and ethical insights of Plato and Aristotle. In fact, I think this P-A-L account is so defensible that I try to update it to current state of the art science in the final chapter of my dissertation, and that updated version is my own belief about how the emotions work in ethics.

Unfortunately, This P-A-L account didn’t exactly set the world on fire at the time. Not long after it was all put into place the Stoics came along and did every thing they could to bury it alive. The fact that I had to write this dissertation at all gives you a good idea of how successful they were. Unfortunately for us.

But before we get to them we have to look at the Epicureans, who have their own strengths and weaknesses to examine.