A Recap and a Rolling Start

As I said last time, Lucretius believes that when the mind is pushed-upon a wave of particles sets in motion, stirring the will. If you read my posts on Plato this should remind you of Plato's similar claims on how the outside world impinges upon the mind and body.

But to "stir the will" has to be explained in physical terms too, and Lucretius comes up with a theoretical physical system called "vital spirit" to do so. More on that later but for now we'll note that the physical substance vital spirit is diffused throughout out the body.

Whatever you call the stuff that moves the body around, the real trick is explaining the interconnectedness of the body and mind, of will and physical action, in a thoroughly materialist, physiologically centered manner. And a good, useful explanation will allow us to understand what it means for the mind to see and understand anything at all. Unless you're up to date on current neurophysiology, this is a pretty tall task.

So yeah, Lucretius has to be pretty bright to come up with such a system nearly 2000 years ago.

But enough back-slapping.

Isn't Physical "Soul" a cop-out?

On Lucretius' account every living thing is replete with "soul", which is completely material, just as much as your foot, ear and every other part of your body. (So don't you who believe in immaterial souls try to hijack this, and don't those of you who eschew such talk get upset!). Material soul is not a cop-out, but I'm going to tell you right now the concept gets pretty hairy so we're going take it nice and slow.

Lucretius actually uses two terms that can be translated into English as "soul": anima, which, for you religious types, is the one traditionally equated with what you mean by soul, and animus, a newer (relatively!) term he uses to make a very novel distinction.

Most simply put, in Lucretius' theory its the difference between the irrational and the rational mind. But even this is hiding some serious complexity. Both the "irrational" anima and the "rational" animus are part of (or two types of) the same stuff, vital spirit. Vital spirit is an admixture of various physical elements and, as I said above, is distributed throughout the body. We'll see that actually it works in a way similar to the central and sympathetic nervous systems. First lets focus on the part of all this that is most accessible to us, the animus, the rational part, what Plato and Aristotle called the psyche.

Animus or Psyche, its the Mind for Plato, Aristotle and Lucretius

For Lucretius, the animus, the rational part of the vital spirit, is responsible for all higher cognitive functions, things like abstract thought and planning ahead. So an able translation of animus is "mind', with all its implications of higher order thought and moral understanding. Lucretius at times also calls it "intellect", "head", "guiding principle" and "dominant force".

As funny as it may seem, Lucretius believed, (like many of his contemporaries, Aristotle and Homer) that mind is located in the middle of the breast. It will be very useful to keep that in mind so you can picture how he can talk about "thinking" in your chest, which will help you to better understand him overall. But let me say it again - like the rest of the vital spirit - mind is composed of matter.

A Primer on Mental Activity

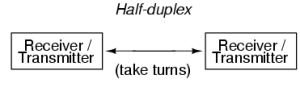

Lucretius makes it clear that vital spirit causes sensibility in us, which allows the mind to have experience. And in order for action to occur, the mind must "judge" the benefits/merits of the results of an action. But this does not have to be done consciously. Just as important, the mind is not a 2-way transmitter (e.g., a walkie talkie) that, for example, "feels" a bug crawling on the skin and then tells the hand to squash it.

NO:

Think about why he is right that this doesn't make sense. If the mind were like a walkie-talkie, by definition only one end at a time can communicate. So if you had a bug on your leg, what would have to happen for you to get rid of it?

First, the body would feel the pressure on your flesh. For your mind to "know it" too would require one of four things:

1) Luckily, at the same moment when the body felt the pressure, the mind happened to not communicating out any messages and so able to receive transmission,

2) The body would not only feel the pressure on the skin, but also "knows" that the mind should stop transmitting and could force it to by accompanying important messages with a message such as "over" to tell the brain to start talking,

3) The body itself would just "know" how to stop the bug (like a reflex),

4) The body is constantly transmitting messages whether or not the mind is in a position to hear them, and sometimes the brain listens in for whatever reason.

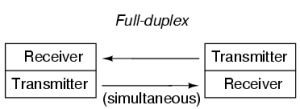

However plausible you find any of these explanations, they raise more questions than they answer. Instead, Lucretius, like Plato and Aristotle, thinks there is a special, interactive and reciprocal communication between the body and the mind (and the emotions), a process I will continue to refer to as duplex communication. The mind and the body are both duplex transmitters, such as cellular phones, which allow two constantly running communications to both be understood by their targets.

YES:

More Details on Mind and Thought

According to Lucretius, mind is able to represent events to itself much faster than they actually occur or would happen. For example, if in real life, if Tim Lincecum throws his two-seam fastball 90 miles per hour, the hitter has .46 seconds to swing at it. Go ahead and imagine that now.

However long you took to visualize it, says Lucretius, it was quite a bit faster than .46 seconds. Another example of the relative speed of mind is how long it takes for the mind to "think ahead", as when you get a joke before its completed. (Here's an article on thought-speed).

I'll get into it more in the next post, but this also relates to something that will be very important to the P-A-L theory (when I finally flesh it out!). Not only is Lucretius really big on how fast mental representation is, he also makes it pretty clear that for the mind to "see" doesn't require deliberation. As he puts it, "within one moment of our sensation, many tinier moments are hidden whose existence reason discovers". And what he means by "discovers" is that the contents of our mental pictures are full of information "right there" and only need to be picked up or picked out. Yet we also superimpose assumptions on the information we process with our minds, so that things not "perceived by the senses" seem to us just like sense perceptions.

But what of it? Well it means that for Lucretius some (maybe even most) things are understood by the senses and not just "passively received" by them. And that means that a lot of what you might call "analysis" or "judging" doesn't require conscious deliberation. And as far as ethics goes, it also means that he is in agreement with Epicurus' saying that in a way we choose to engage in poor or irrational behavior because we often have a strong will to impose questionable - or even flat out wrong - interpretations on the things we see and hear.

We'll come back next time to look at the anima and more fully understand vital spirit.

No comments:

Post a Comment