Introduction

You’ve probably never heard of philosopher and theologian (also trained in medicine) Richard Cumberland, but he was highly respected in his time, particularly for his work in political philosophy. He had a deep interest in the way the natural world worked and in identifying natural ethical laws. He followed many of his contemporaries in a spending tremendous amount of time and ink arguing against the philosophy of Thomas Hobbes (even though he shared Hobbes’ mechanistic bent). But the second most influential philosophy on Cumberland was Descartes’ intricate dualist theory of mind and emotions

Cumberland followed but also improved up on the Cartesian theory but his efforts led thinkers such as Shaftesbury, Hutcheson, and Hume to repudiate the cognitive line of thinking on emotions and morality, paving the way for William James’ wholly visceral account at the end of the 19th century.

Descartes’ Influence

Cumberland accepts in principle Descartes’ mechanistic philosophy, is an earnest metaphysical dualist, and is an even more avid student of anatomy and physiology than Descartes. But even as he works to further the general Cartesian project on the nature of the emotions he goes beyond Descartes’ theory in ways that undermine core Cartesian beliefs and set the stage for the twin emergences of fundamentally physiological theories of emotion and the sentimentalist ethics. He did so by intentionally making the physical processes of the body even more central to the creation of emotions than Descartes did, and further clouding the role of a separate mind in generating emotions, even as he worked hard to protect the ‘fact’ that the mind in fact did exist separately.

The first significant improvement over Descartes’ positions and arguments is that he starts from the point of view that we ought to compare the similarities and differences between human and animal anatomy and physiology. This immediately makes him less dependent than Descartes on the concept that the soul makes humans fundamentally different from animals.

This starting point also has the benefit of letting him:

1) Allow for animal souls, beliefs and emotions

2) Differ with Descartes on the nature of human will and what it can do

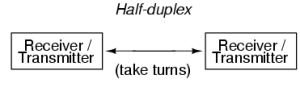

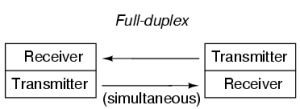

3) Be seriously concerned with a duplex theory of communication between the brain and the viscera

4) Start with a basic but well-founded conception of two types of emotions

5) Argue that, properly harnessed, emotions are a wonderful thing

As I explain these five aspects of Cumberland’s work on the emotions we’ll see the good and the bad in it, understand how it extends and grows out of Descartes’ work, and how it sets the stage for the theories of Shaftesbury and Hutcheson, and sentimentalism.

How you to cut up the world

Descartes famously – and wrongly – cuts the world up between bodies-qua-machines and human minds (souls). Cumberland, however, takes a more nuanced approach to his ontology, which gives him what amounts to a quantum leap in theoretical sophistication and explanatory power.

Its so groundbreaking for two reasons: first, he’s willing to take human animal physiology seriously, believing that its not right to just think of our bodies as basically the same sort of machine; second, he groups animals with humans as things with mental lives, which means that the world is cut up between animals and humans on one hand and everything else on the other. This fundamentally alters what he can do when he takes up the nature of emotions.

Human and animal bodies are interesting

Cumberland saw what Descartes either missed or ignored; bodies –animal as well as human – are sources of sensation and perception. It’s hard to overstate the importance of Cumberland seeing that animals sense and perceive much as humans do, but as always we’ll focus on the importance for understanding emotions in ethics.

Recall that Descartes’ first error forced him to pack so many abilities into the soul, and make the soul so different than the body, that he was simply unable to tie the mind and the body together convincingly. With his view of human anatomy, Cumberland avoids a lot of this damage, even if he doesn’t completely escape it.

Cumberland remains a dualist, and his version doesn’t convince anyone that the position is true, but it does also go a long way toward helping him avoid the Second and Third Cartesian errors. That’s because his initial position allows him to account for body-level consciousness, which in turn lets him give up a rudimentary but legitimate account of how there are two types of emotions, and how the brain and viscera, mind and body, communicate via feedback loop.

Cumberland seems fine with thinking of animals as having souls, and so beliefs and emotions of a kind. That’s great, but he’s still a Cartesian in that he sees man as special due to our “spiritual, incorporeal, godlike” minds. That means he doesn’t completely avoid the First Cartesian error, but he makes a connection between mind and body that Descartes couldn’t nail down and that gives him greater latitude for discussing emotions.

Duplex Communication

Cumberland’s desire to map communication between the brain and heart, along with his advanced-for-the-time knowledge of anatomy and physiology lead him to a dramatic change in the relative importance of the brain compared to the soul; the brain does much more work than in Descartes. If Cumberland can consistently attribute mental work to the brain rather than the soul, he can be said to have a duplex theory of communication between mind and body, something methodologically impossible for Descartes.

But at the very least, he goes beyond Descartes’ view that the soul/mind is a thinking thing that passively receives information, magically manipulates the pineal gland and thereby the body. Cumberland doesn’t see abstract thought as the only function of the soul but still argues that reason, through the emotions it helps beget, has a serious role to play in creating action, and he can offer a physical reason how.

Two types of Emotion

Cumberland identifies two types of emotion, The first, ‘passions’, are the intense feeling about or the intense force with, the vehemence with which we do – or refuse to do – things. The second type, which he calls ‘emotion’, are the visible disturbances of the body that go along with the passions.

To understand how emotion and passion relate, I’ll explain how Cumberland views cognition and volition, but for now let’s just say that the will is a function of the mind, different than abstract thinking, it is the agent for the thing that does the ‘real work’, and the strong feeling one has about the actions.

Emotions can be Wonderful

Finally, unlike Descartes, Cumberland believes that properly harnessed emotions are necessary for being moral. One reason for this is a basic disagreement with Stoicism. As he explains, mankind would be better off “left to the sentiments of nature” instead of being forced into a “hardened virtue” that doesn’t recognize that the passions are “divine and gracious…divine virtues, if their objects be things divine” and allowing for sympathy with our fellow man.

Next time we'll unpack this a bit more and then move on to the rise of sentimentalism.